A pool game in Brazil popularly known as ‘sinuquinha’ is expanding in the country by using strategies and even structures similar to those found in esports.

The Copa Mundo da Sinuca, the fourth edition of community pool game Mundo da Sinuca, came to an end earlier this month.

The event was organised in partnership with the BMS group, a holding company specialising in the gaming industry, and sponsored by Betway, which grew its presence initially by supporting esports organisations and events.

With an organisational structure that resembles top esports events, the tournament was streamed on YouTube with casters, commentators, and guests, peaking at over 38,000 simultaneous viewers during the grand final between Márcio “Cobrinha” Fontes and Josué “Baianinho de Mauá” Silva, two of the leading players of the scene.

BMS, which handles esports production for Liga NFA — the biggest independent Free Fire tournament — is now expanding as an entertainment hub beyond gaming.

“We were introduced to the competitive sinuquinha world through an employee and found it an interesting product. So we contacted the organisers and further studied it before diving in,” BMS Commercial Director Samuel Gonçalves told Esports Insider.

Although the professional competitive scene is still gaining relevance, sinuquinha is far from unknown in Brazil. On the contrary, the sinuquinha table — which is smaller than regular pool tables — can easily be found in any Brazilian city, being the most traditional entertainment in local pubs, parties and meetings. That makes the game immensely popular in the country — most Brazilians will have played at least once.

The founder of the tournament was Paulo “PH” Carmo, owner of the Mundo da Sinuca website. “It all started through some highlights and shots from our players going viral online,” Carmo told Esports Insider. “Sinuca doesn’t have much media anywhere, and so we found a place on YouTube. We have shown ourselves in this media, so other unconventional sports would also be able to grow over here.”

A similar approach has been used by the chess community since 2020. Despite not fitting conventional definitions of esports, chess entities have hosted esports tournaments, signed endemic esports sponsors, and used online channels like Twitch and YouTube to grow considerably outside the traditional chess community. In December 2020, esports organisation FURIA signed grandmaster chess player Krikor Mekhitarian as a talent.

Having previously worked at Garena building the Free Fire community in Brazil, Gonçalves set out to use the same strategies for the mobile game to develop the sinuquinha scene.

BMS was involved in the design, production, communication, and even career consultancy for players. It led to the foundation of a structured league, the Brazilian League of Sinuquinha (LBS), which established a steady calendar and made it possible for new talent to emerge.

It is even possible to draw parallels between Free Fire and the sinuquinha due to their accessibility. Just as Garena’s mobile battle royale became popular thanks to being playable even on the simplest smartphones, the sinuquinha tables’ availability makes it easy for people to start playing and to practice.

The fancy clothes and glamorous settings seen in world-class pool tournaments are also absent, giving sinuquinha the potential to create life-changing opportunities in the country, just as Free Fire and football have.

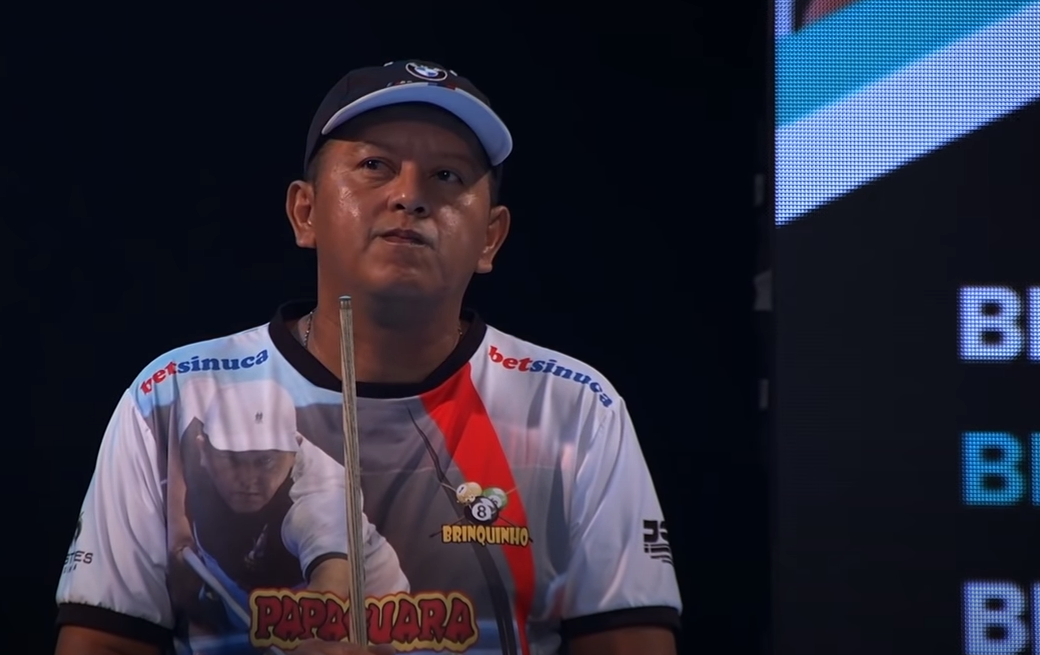

Arthur “Brinquinho” Santos, winner of the second edition of the Copa Mundo da Sinuca, is a living example of how sinuquinha can change lives. “I worked as a bus ticket inspector in Brasilia in 1995, when I started taking a shot at sinuca,” he told Esports Insider, adding that it was only in 2012 that he could make a living from the game.

Similar stories are not difficult to find among elite Free Fire players. Even the world’s biggest star of the mobile game, Bruno “Nobru” Goes, chosen as the 2021 Personality of the Year at the Esports Awards, publicly said he had his entire family’s life changed for the better through Free Fire.

Santos’ story, though, goes even deeper: “Today many people know me, there are many fans around Brazil, even children. At first, I used to drink [alcohol], but today I don’t drink anymore, it’s been three and a half years since I stopped. My sponsors don’t want to relate the player with drinking, so I even stopped drinking because of them. I need to be an example.”

Ricardo Lopes, Vice-President of the São Paulo Sinuca Federation, told Esports Insider that these new strategies sinuquinha is employing are helping change the game for the better. “What makes me happy is the evolution of the players, from the skill level to the respect of their opponents and the respect of who is watching, because sinuquinha or sinuca in Brazil was always seen as a trickster’s game.”

“Today this is being changed because people are seeing events never seen before and the respect of the players when they shake hands after a match. Way before, in the beginning, there were shirtless, drunk players, etc. Now, that is over. You see posture in the players.”

By incorporating many of the same strategies that esports tournaments have used to thrive, events like the Copa Mundo da Sinuca have taken the game ‘to another level,’ Lopes added, bringing investors to the scene.

RELATED: Garena signs deal with Brazilian retail giant Casas Bahia

Before Betway stepped in (brought in by way of Brazilian marketing agency Druid), the scene already held several sponsorships from smaller local businesses. The most prominent of them is Papaguara, a biscuit brand that invested in the professionalisation of the scene as a whole, sponsoring both tournaments and players.

Santos, for example, is one of Papaguara’s players. Besides the biscuit brand, he is also sponsored by other local businesses — from betting website Betsinuca to the dentist’s office Lucas Dente. His living wage is complemented by fees and prizes he receives from events around Brazil. The fourth Copa Mundo da Sinuca provided a participation fee to all of its players.

On the surface, Sinuquinha appears far removed from the esports industry. However, esports was born and raised in an online environment, and so it developed unique strategies for engaging and growing communities online. Now, those strategies are being smartly leveraged by non-traditional and even non-gaming tournaments outside the esports bubble.

It is evidence that, while the esports industry itself develops, it is also contributing to the bigger picture of digital entertainment by pioneering new engagement strategies that can be used in different scenes.

Sinuquinha has now found its space in Brazil. But like sinuquinha, and chess before it, other out-of-the-box traditional games around the world may start using esports as a model to prosper.

[primis_video widget=”5183″]

[maxbutton id=”22″ ]