Scholastic esports, a general term used to describe competitive gaming in the educational system, has changed significantly over the last few years.

The first esports degree was launched in 2018 by UK institution Staffordshire University, with a multitude of universities across the world shortly following suit. Esports has not only made its way into higher education, high school esports clubs are gaining momentum and esports education courses below university levels have started to be implemented.

However, the scale and structure of scholastic esports drastically differs from country to country.

Gerald Solomon, Founder and Executive Director of NASEF (Network of Academic and Scholastic Esports Federations), described the scholastic esports scene prior to the organisation’s launch in 2018 as “primarily nonexistent” — with the focus largely on the competitive scene. As an education partner to the IESF, NASEF has affiliates in 33 countries with the non-profit’s aim, according to Solomon, being to make its project-based learning model “mainstream in educational systems worldwide”.

Esports Insider, with the help of NASEF, has taken a look at four different scholastic esports ecosystems — the UK, the US, Japan and South Africa — to showcase different strategies that are currently being used to merge the education and esports sectors.

The United States

For traditional sports, the US has one of the most widely recognised collegiate structures in the world, with scholarships that reward competitive excellence and an array of educational opportunities. This level of structure extends all the way from Kindergarten to 12th grade (5-18) from a competitive standpoint. So, it makes sense that when it comes to esports and education, the US is seen as one of the biggest potential markets.

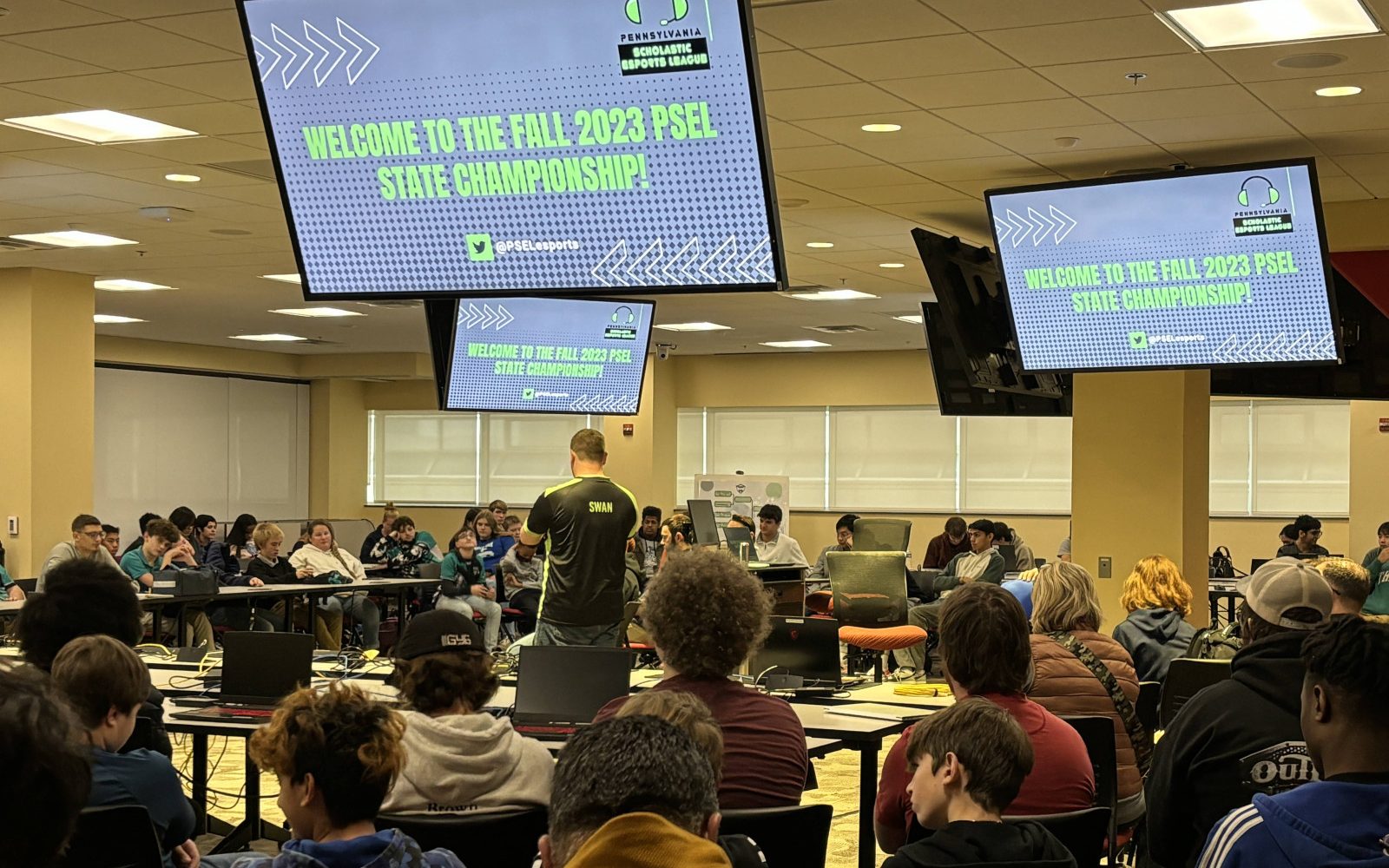

Kammas Kersch, Leader of the Pennsylvania Scholastic Esports League (PSEL), noted that the current scholastic esports ecosystem in the US is “rapidly evolving” with educator-led organisations helping build communities and creating relationships with education institutions to provide greater opportunities for students.

“What we have seen is that educators are taking the lead in building out opportunities for students and fellow educators to see esports as not only a competitive experience, but a learning experience,” she explained. “Here in Pennsylvania, we are proud of the esports ecosystem we have been building.”

As Kersch highlighted there are two core sub-sectors in scholastic esports — education and competition. As a result, different institutions will have different priorities based on which sector they want to focus on, how esports is perceived, and what country these initiatives will take place.

In the US, this becomes even more fragmented with there being a multitude of educational bodies across different states, all of which prioritise the most effective for their community. Given differing state opinions on the importance of esports, the level of investment can vary massively as well.

For example, over the years the state of Georgia has been a public advocate of esports which is shown through the range of educational and competitive initiatives that have occurred. California’s governing body of high school sports, the California Interscholastic Federation (CIF), runs a statewide esports initiative which includes an in-person championship final. Additionally, California has a separately approved esports-centric classroom curriculum.

However, Kersch does highlight that in the K-12 sector, US educational stakeholders are looking at esports as an opportunity to promote STEM, social-emotional learning and career readiness.

“Formally and informally, K-12 educators are creating authentic learning experiences for students through esports, which many times happens as they are participating in a competitive environment.”

Ultimately the next step for the US when it comes to scholastic esports will be to increase opportunities across the entire country. This can be done through the development of state-level leagues — encouraging other areas to invest in the competitive esports ecosystem — or through the introduction of courses related to scholastic esports to more parts of the US.

Kersch added: “I think the next development that we’ll see will be increased access for students. Over the last several years, we have seen the development and launch of state-level leagues across the country, such as Garden State Esports (NJ), Texsef (TX), Pennsylvania Scholastic Esports League (PA), and many more.”

The UK

The UK is another country that has an extensive higher education and collegiate esports ecosystem. However, the UK’s scholastic esports landscape is still an emerging ecosystem that has yet to fully reach its potential.

The biggest competitive structure of scholastic esports in the UK is the British Esports Federation Students Championships, which provides weekly competitions for 12+ students to compete against other schools and colleges. An increasingly common initiative as well is the launch of after-school esports clubs, allowing students to use esports as a social activity providing them with a space to engage in the scene.

James Fraser-Murison, Esports Insider’s Esports Education Advisor, noted that the UK “is very lucky” to have both competitive and educational options available to many students who are keen to engage in the esports space.

“Both the UAL (University of Arts London) and Pearson have courses that allow access to esports education from year 10 (14+) and above, all the way to specific degree-level programmes,” he said.

As Murison alluded to, perhaps one of the biggest educational esports achievements for the UK’s scholastic scene is Pearson’s Esports BTEC. Launched in 2020, the BTEC has enabled educational institutions to teach esports industry skills to those 16 and over whilst offering an academic qualification at the end.

With the development of scholastic esports gaining traction, the next step for the UK scene is to keep demonstrating its potential. By showcasing how scholastic esports can develop essential skills, Murison hopes to see more government investment in the future as well as greater competitive opportunities.

He concluded: “The general awareness of scholastic esports continues to grow positively and is seen as a way to introduce not only students from all backgrounds, but businesses as well to look differently at how they could recruit young people with these essential and transferable skills into the modern day workforce.

“I hope to see all types of educational institutes embrace the opportunities esports can bring to all learners and use it to create new teams and new types of competitive competition within their walls. Not instead of, but alongside the likes of football, netball and basketball.”

South Africa

The level of interest in esports in education will primarily come down to the perception of competitive gaming amongst relevant authorities, whether that be the country’s government or key educational authorities in the field.

According to Ruckus Media’s Founder, Marc Joubert, who is currently utilising NASEF’s programme in South Africa, the local scholastic esports scene is fragmented with many schools unable to leverage esports due to a lack of resources (primarily PCs/Consoles). While attempts have been made by local esports organisations and private schools to develop competitive opportunities within the scholastic system, Joubert noted that these endeavours have yet to find a solid footing.

“There is no ecosystem. Everyone is trying to own one little piece of the puzzle with no one looking holistically,” he explained. “From a government perspective; firstly, our Dept of Sports, Arts and Culture have not even begun the discussions on whether esports is classified as a sport. Secondly, our Education Department struggles with concepts like child placement in schools and getting books to schools on time — esports integration is like space travel.”

From an educational standpoint, the scholastic esports scene in South Africa is even more bare with Jourbert claiming that “NASEF is the first attempt at bringing actual esports in as a learning concept.”

However, despite South Africa’s lack of regional esports development — in a 2022 interview with Esports Insider South African esports desk host Sam ‘Tech Girl’ Wright described the scene as “the European esports scene 10 years ago” — there is an appetite for esports. After rolling out NASEF’s scholastic esports programme for 10 months, Joubert highlighted that the development of esports clubs can benefit the country’s scholastic ecosystem and create greater opportunities.

“The most effective way is to develop it from the bottom – up, through the establishment of esports clubs,” he said. “This will automatically create fertile ground for consistent events and will eventually start forcing tertiary education to catch up.”

Whilst South Africa’s scholastic scene is still in its infancy, this creates opportunities to develop the ecosystem in the right manner by being able to learn from the trials and tribulations that other more developed countries have undergone.

Japan

Aligning with NASEF’s vision to develop scholastic esports ecosystems worldwide, Japan is a country looking to establish itself in the scene.

Whilst there is an emphasis on both educational and competitive initiatives, the onus seems to primarily lie on the competitive ecosystem. However, according to Yoshi Tsuboyama, an Esports Program Director at NASEF Japan, “there is a movement to incorporate educational esports into schools in the future.”

By adopting a similar structure to NASEF’s US operations the ultimate aim is to create more education opportunities within the scene. However, Tsuboyama highlights that breaking into educational institutions is a difficult process.

He explained: “Japan has high school and university entrance exams (paper tests), and subjects and activities not related to these exams are often neglected. Both from parents and teachers.

“However, recently, esports scholarships at universities and acceptance into universities based on what one has learned through esports have been gaining recognition, and progress is being made, albeit gradually.”

To tackle the perception of esports at an educational level in Japan, Tsuboyama believes that it’s all about showing the benefits of esports education programmes through case studies in schools.

“No one wants to be the first, and people often ask what others are doing, or whether schools in the same area have introduced the system,” he said. “Therefore, it is thought that more and more examples from school sites and disseminating them will spread.”

Given Japan’s growing competitive esports scene, the potential for high school esports is apparent. This is why since its launch in 2020, NASEF Japan has looked to introduce the value of esports in high schools alongside the JHSEF (Japan High School Esports Federation).

NASEF also noted to Esports Insider that new, non-traditional learning modalities — like project-based learning (PBL) — are gaining traction among educators in NASEF Japan and other NASEF scholastic esports programmes around the world.

This method of teaching allows students to be offered a learning challenge by teachers, who serve as guides and resources. Students are encouraged to find resources, develop hypotheses, conduct research and experiments, analyse data and then present their findings. This aims to develop itinerant skills while engaging in the project alongside educators, industry professionals and local administrators.

These modalities have begun inspiring teachers to consider other ways to teach common topics, such as adding esports-infused elements into required subjects.