Despite being a relatively small country with a population of roughly 10m, Portugal has slowly shown signs of becoming a potential esports hub in Europe — akin to the likes of France and Spain.

The esports market in Portugal is projected to reach a revenue of €16.8m (~£14.3m) in 2024, according to Statista. It is expected to exhibit an annual growth rate of 6.54% (CAGR 2024-2028), resulting in a projected market volume of €21.7m (~£18.5m) by 2028.

It is, therefore, unsurprising that organisations and stakeholders have begun to emerge and develop in the country as its reputation and positioning in the global industry increases. BLAST Counter-Strike tournaments have graced the country and local teams, such as SAW, are competing on international stages. Step by step, the esports industry’s eyes are looking at Portugal, and in tandem, there is more movement to bolster the ecosystem both locally and nationally.

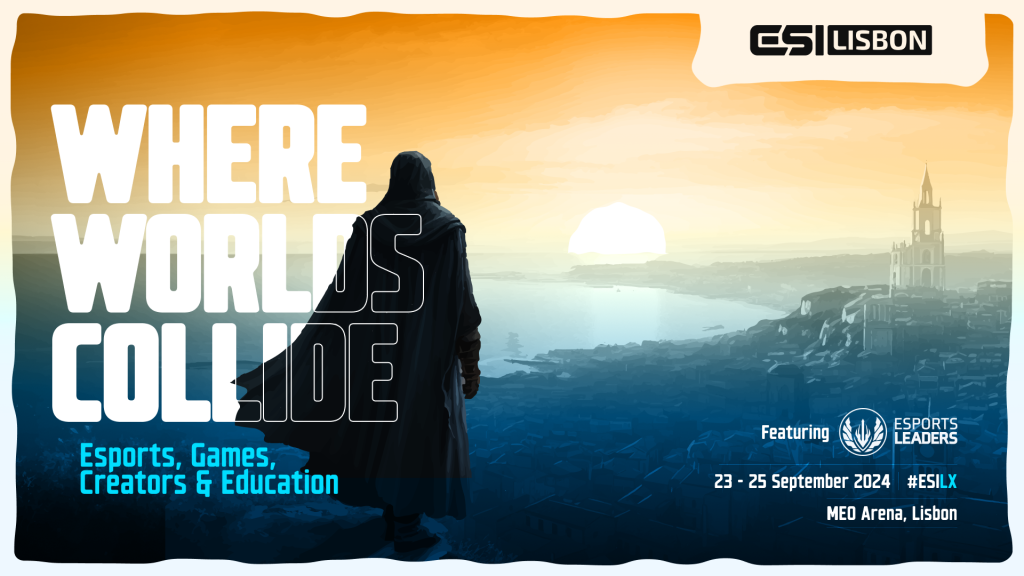

Ahead of ESI Events’ own expansion into Portugal through its international, flagship event, ESI Lisbon, from September 23rd to 25th, let’s dive into the nation’s esports ecosystem.

Portugal’s esports pillars

Portugal’s esports ecosystem consists of a myriad of stakeholders, varying in size and specialisation. For instance, Portuguese esports organisation SAW has been making waves in the international Counter-Strike scene since a successful 2024 BLAST Premier Spring season and Intel Extreme Masters (IEM) Cologne 2024 run.

Similar to a lot of European countries, Counter-Strike is the flagship esports title in Portugal. According to Esportsearnings, CS:GO accounts for nearly $1m (~£852,000) of the combined $4.95m (~£3.81m) in prize money awarded to Portuguese athletes. Sports simulation games make up another sizable chunk of the market fuelled by local sports and esports entities creating rosters in EA Sports FC, NBA 2K and Rocket League.

Some of the most notable among them are football team Sporting CP, which holds a roster in EA Sports FC and Rocket League, Luna Galaxy, founded by professional footballer Diogo Jota (and previously known as Diogo Jota Esports), and Betclic Apogee. Luna Galaxy just won the EA FC competition at the Esports World Cup in Riyadh, taking home $300,000 (~£229,000) of the $1,000,000 (~£763,700) prize pool.

In terms of entities producing esports content, RTP Arena, the esports department of Portuguese national television company RTP, has become a major player in the region.

According to RTP Arena’s Content Manager Gonçalo Louro, the department broadcasts international esports tournaments for the Portuguese audience while creating various content formats: “We have a tech talk show. We have a gaming talk show where we talk about the latest news in gaming and we have a lot of different content released on our social media like TikTok, Instagram and YouTube as well. We also have written content, mainly journalistic pieces, on the latest news in esports and gaming.”

E2Tech is another major player in the market. Since its foundation in 2007, the esports event producer has grown to host some of the nation’s most notable IPs, including video game festival Lisboa Games Week and the international competitive series XL Games.

Non-profit esports organisation Grow uP eSports dates back to the early 2000s and owns the GIRLGAMER Festival, an esports and gaming event series dedicated to celebrating and promoting ‘women’s competitiveness in esports’.

“We wanted to do something special and we wanted to do something meaningful for the entire ecosystem,” said ESI Hall of Fame Award Winner Telmo Silva, who founded Grow uP eSports at the age of 16.

“We want to do something that can change the lives of women playing competitively – create a safe platform and a safe environment for them to compete. It’s for them to show their talent because with this platform, we can create the role models for younger generations.”

Grow uP eSports also contributes to the Portuguese esports system through social impact and education initiatives. In 2011, the organisation became the first Portuguese esports entity to be financially supported by the government. 10 years later, Grow uP opened its first gaming facility focused on youth work in collaboration with Portuguese municipality Sintra. To bolster its educational impact, Grow uP also partnered with football club Casa Pia A.C. last year.

Portugal’s esports industry is supported by two major bodies. — FEPODELE and FPDE — with both federations working towards the recognition of competitive gaming by the Portuguese government.

“It’s a movement similar to a lot of other national esports federations, so we’re mainly looking into our main goal right now, especially in Portugal: to make sure that our government recognises esports as a sport,” stated Pedro Honório da Silva, President of FPDE. “We believe there’s no regulation about a number of things. And we believe that there should be.”

Rui Alexandre Jesus, General Assembly President of FEPODELE, explained one of the federation’s main objectives: “You need a referee. […] You need someone to say ‘Whoa, whoa, calm down. Let’s take a whistle. Let’s sit. Let’s talk.’ You need someone to do that. Our biggest challenge now is to try to find that referee.”

More recently, the Observatory of Gaming and Esports (OGE) was also founded to provide an independent party monitoring the local esports scene and its issues. This was established in Óbidos, and ‘was born from the need felt by some professionals to have access to information about this industry in Portugal’ according to an article about it on CM Obidos. “An observatory is needed to bring people together in an independent way,” Jesus explained.

“We are starting to develop it and I sincerely believe that that could be the positive future and help to a bright future of esports in Portugal.”

Portugal as an esports hub

Throughout the relatively short history of esports, several destinations worldwide have developed so-called ‘esports hubs’. Arguably, the most prominent esports hub in the world is South Korea.

South Korea’s government took a leading role in the country’s meteoric rise as an esports destination through the recognition of esports as a legitimate sport and the creation of advantageous infrastructures. With broad access to high-speed internet and gaming consoles through gaming cafes, known as PC bangs, the country managed to establish esports and gaming as a core social activity before the beginning of this century. Furthermore, the Korea e-Sports Association (KeSPA), the country’s esports government body, was established as early as 2000.

Esports quickly cemented itself as a prolific form of sports and entertainment within the country’s society. Commencing in 2018, the South Korean government invested in the construction of 500-1000-seat esports stadiums in Busan, Daejeon and Gwangju, driven by The Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism. In the same year, South Korea established its first national team to compete in the Jakarta-Palembang Asian Games. Today, several municipalities and cities have yearly budgets allocated to the development of esports.

However, South Korea’s example shines a light on perhaps Portugal’s biggest barrier. Until recently, Portugal’s government has taken little interest in the local esports industry. The lack of governmental support also coincides with common stigmas surrounding esports and gaming.

Competitive gaming is still an unknown variable for many members of Portugal’s society. As a result, local companies hesitate to invest in the field.

This tricky environment sees Portuguese esports stakeholders struggle to find profitable sponsorships and partnerships. According to FPDE’s da Silva, the weak local economy and difficulty in creating valuable activations for interested brands also plays a role. The FPDE President further shared that even international brands may not offer lucrative sponsorship deals, as their budgets tend to prioritise larger esports markets.

“It’s extremely rare to have a double-digit sponsorship package with any sponsor. So we’re talking about the vast majority of sponsorships being below €5,000 (~£4,257). It’s very difficult then to sustain oneself or, for instance, create a competition with a €5,000 prize pool.”

RTP’s Louro believes that esports’ market correction, commonly referred to as the ‘esports winter‘, also impacted Portugal’s competitive gaming industry: “Even in Portugal, we felt that we found some brands retreating a little bit, trying to not invest as much money.

“Just like the big names suffered, we also suffered.”

Despite glaring challenges, Portugal’s market has several characteristics that position itself as a potential esports hub. Grow uP eSports’ Telmo pointed out the country’s broad access to fast internet connectivity — which other major European esports markets like Germany, lack — provides a major advantage.

Da Silva also highlighted Portugal’s geopolitical location. He believes Portugal may act as a bridge between the world’s continents. With decent proximity to Brazilian and US esports markets, the country may become a popular destination for international events.

FPDE’s President, further argues that the nation’s lenient visa policies and tourism industry might make Portugal an attractive event location. Similarly, the country offers cost-efficient resources, allowing organisers to host events cheaper than in other European nations. The local fandom, especially in Counter-Strike, might also play a key role.

Despite these positives, Portugal has yet to become a regular home for major international events. So far, two BLAST competitions have been held in the country. According to Esports Charts, the BLAST Pro Series Lisbon in 2018 peaked at 236,645 viewers. Four years later, the BLAST Premier Spring Finals more than tripled that number, garnering 762,885 peak viewers. BLAST also announced its return to Portugal in 2025, serving as evidence of the country’s suitability for hosting tournaments.

One major event that is heading to Portugal is ESI Events’ flagship event, ESI Lisbon. From September 23rd to 25th, ESI Lisbon invites gaming, esports, and creator economy leaders from Portugal and around the world to network and discuss relevant opportunities and challenges in the esports industry. These discussions will take place at the event’s exhibition space and stages located in the MEO Arena.

Alongside the attendance of Portuguese stakeholders RTP, Grow uP eSports, FEPODELE and FPDE, international brands and organisations, such as Visit Raleigh, GRID, Samsung Ads and Spectatr are supporting the event as sponsors. The conference will also feature the debut Esports Leaders, which features senior-level executives from major game publishers, esports teams, tournament operators, brands, agencies and more. You can see the full attendee list here.

RTP’s Louro, in particular, considers ESI Lisbon to be a vital opportunity for the local ecosystem: “It allows some of our local businesses to take a closer look at what’s done on a bigger scale internationally and try to adopt those ideologies, those practices to the current market in Portugal.”

Future of Portuguese esports

With the government’s role yet undefined, the Portuguese esports ecosystem struggles to attain balance and sustainability. However, 2024 seems to be a potential turning point. During a parliamentary conference — supported by the Socialist Party and promoted by FPDE — on July 2nd, politicians and relevant stakeholders discussed the creation of a regulatory framework for esports in the country. André Batista, part of the Socialist Party, has long been an advocate for the esports industry and will provide opening remarks at ESI Lisbon ahead of a keynote from esports powerhouse T1.

Jesus remarked that the political efforts of FEPODELE and other key players have finally found fertile ground: “In the last eight years, what I’ve achieved specifically in this project — the role of any National Federation, I believe — is to convince the government. In Portugal, we’ve now achieved the start of the legislative process because it was a unanimous recognition of everyone that some rules should be applied now.”

Da Silva has noticed a similar shift: “There will be no legislation done in a short amount of time. This will take its time, but at least there’s a lot of conversation going on, a lot of traction, a lot of political attention. I think it is happening but when exactly remains to be seen. We predict that it’s probably going to take about 12 months until we get some sort of actual legislation around this.”

Louro emphasised: “We have the talent here. We just need more support, and I think the government could have a really big impact by making people feel more secure. I think as soon as that regulation starts to exist, there will be more brands coming in; there will be more security for some talent to become professional players.”

Da Silva hopes that future governmental action could help stabilise the ecosystem through public esports initiatives and funding, enabling struggling organisations to be less dependent on sponsorships. Grow uP eSports is a leading example as the organisation predominantly relies on public funding through its collaboration with the Portuguese Institute of Youth and Sports.

Another area of progress has been the destigmatisation of esports and raising awareness for the positive impact of competitive gaming on Portugal’s society and economy. As Grow uP eSports’ Telmo illustrates: “Children saw [our youth house] as a safe space. And we also work with their parents. Some of the parents now go with the kids to play with them. The parents support their kids going to our arena because, just like their kids, they started seeing it as a safe space.”

All in all, Portuguese esports stakeholders appear to be cautiously optimistic regarding the growth potential of their scene. Some believe the country is certain to develop into an international hub in the future, others think the related roadblocks might make relevancy beyond Europe difficult.

However, as highlighted by Louro, one thing is for sure: “Esports is not the future. Gaming is not the future. Esports and gaming are the present.”