When we discuss value in the Western esports industry, what are we usually referring to? And where is it found?

Industry valuations are not the concern of this discussion; some believe the sector is worth around $1.1 billion while others think it’s closer to $25bn. Some academics think general publisher revenue from games considered ‘esports’ — including the top 20 percent of esports titles in terms of revenue generated — should be included in the calculation, while Newzoo’s definitions are more conservative. The goal of this essay is not to explore that.

The goal here is to pinpoint exactly what we mean when we advertise the ‘esports industry’ in the West as a singular entity — top-tier competition in titles like League of Legends, CS:GO and Dota 2 — and to ponder whether bunching titles together leads to inflated assessments.

Inequality among esports titles

The Western esports industry, as we conceptualise it, is fundamentally unequal. League of Legends is the obvious outlier. In fact, by almost every metric, League of Legends is by far the most successful esport; it dominates viewership charts every year and secures the most lucrative sponsorship deals. Without League, the industry’s total size would prune. CS:GO is clearly second in the West but is still a way behind League. Dota 2 is hugely popular in the Russian-speaking world, but is still some way off League and CS:GO in the rest of Europe and North America.

Viewership stats have been notoriously fraught in esports for years (though it is improving). According to Esports Charts, Worlds 2020 had an average concurrent viewership of 1,113,702 across the main event spanning an entire month (including Asian audience but excluding data from Chinese platforms) — by far the most-watched esports event of last year. 16 of the 20 most-watched esports events of all time are League of Legends or CS:GO events (in terms of hours watched; average concurrent viewership/average minute audience statistics have not always been available).

The gap between two esports — League and CS:GO — and all other titles in the West is more like a chasm, with the exception of Dota 2 in the CIS region. And indeed, the gap between the two front-runners is significant. This shows how great League of Legends is, and how meaningful pro Counter Strike continues to be 20 years on. What this does not show, however, is how the rest of the industry is doing.

Compared to gaming generally, esports is a footnote. As of 2020, Mordor Intelligence reckons that gaming will reach a total value of $256.97bn by 2025. The figure in 2019 was $151.55bn. In the US alone, the video game market has a value of $60.4 billion, according to Statista (as of 2020). Gaming is already a giant.

Compare this to esports: if we use Newzoo’s definition (which avoids the issue of sweeping, contentious definitions and captures only that which this article concerns: generally agreed-upon esports titles), the esports industry should have reached a total value of $1.1bn in 2020. Esports, however you slice it, is a small portion of gaming revenue.

When do we expect the hundreds of millions of Western gamers that play Call of Duty, FIFA, Fortnite, Overwatch and so on, that do not currently care about esports, to start caring? The answer might be that for most titles, they won’t. These titles have accrued enormous player bases over many years, and yet their pro scenes lag behind.

If the Call of Duty League were assessed on its own merits, and not seen as part of a burgeoning ecosystem, would investors have forked out tens of millions for a spot? When scrutinised, it becomes clear that CoD esports is built on shaky ground.

Our bunching together of the ‘esports industry’ is dictating the value of specific titles — not the other way around. This is a concern.

Esports — despite attention-grabbing headlines of inflated or misrepresented stats — isn’t close to gaming in terms of fan volume and active participants, perhaps with the exception of League of Legends. 68 percent of League fans watch competitive matches — compared to CS:GO’s 51 percent — and League was the world’s most popular PC game as of November 2020. Last year, Worlds blew every other event out of the water in terms of viewership (particularly in the West). League stands alone as an esport.

Despite the relentlessly positive forecasts, how much of the industry would be salvageable without League of Legends and CS:GO? When we wax lyrical about the esports steeplechase, at least in the West, we are selling tickets en masse for a two-horse race in which one is the clear favourite (again, Dota 2 does very well in CIS — perhaps even as well as League and CS:GO — but generally speaking, CS:GO and League are far ahead in most of the Western world). League and CS:GO are, to some extent, the Western esports industry.

This may change in the coming years, such is the fast-paced nature of the sector. But as of right now, that’s where the value is.

Leaning on esports’ stalwarts

In our haste to present the esports industry as a winner to outsiders (and perhaps to ourselves), we seem to have forgotten that it’s made up of various titles — titles that are ever-changing and highly unpredictable.

Newzoo reckons the global esports audience should have reached 495 million in 2020. Yet 55 percent of that figure, 272.2 million, is made up of so-called ‘occasional viewers’ — those that watch esports less than once a month — something Newzoo, despite criticism, outlines explicitly. However, stats such as these are often used by outlets to aggrandise the industry without being at all scrutinised.

“Newzoo gets people excited about our industry,” one esports industry CEO told Esports Insider. “But their data can be generous.” According to a Kotaku report from May 2019, some executives consider Newzoo data ‘too opaque’ to be seen as legitimate. Clearly, some feel that many industry stats are untrustworthy.

Esports Insider reached out to Newzoo for comment on the above. Remer Rietkerk, Head of Esports at Newzoo, responded with the following:

“We believe it’s important to differentiate between Esports Enthusiasts and Occasional Viewers, which is why we always show the breakdown in our key numbers charts rather than presenting the total number. While esports enthusiasts do represent the core value driver of the market, occasional viewers make up a long-tail which have a significant value-add of their own. The most exciting moments in esports — and sports, for that matter — tend to be based around knock-out events, which happen infrequently, rather than seasonal league play, which happens more frequently.

“Based on our research of gamers and esports fans in 32 countries, there is a significant chunk of people who watch esports less than once a month — for events such as IEM Katowice or The International. This number is important for our clients for many reasons, such as opportunity space in converting infrequent viewers into more regular viewers. We do our best to correct misinterpretation where we encounter it and we strive to make our definitions and methodology as clear and transparent as possible.”

Wherever you stand on Newzoo’s methodology, esports stats have repeatedly been blown out of proportion. Everybody has heard the Super Bowl comparisons. In 2019 CNBC ran the headline ‘League of Legends gets more viewers than Super Bowl’, comparing Worlds’ 100 million unique viewers — an incredibly thin, untrustworthy metric when used alone — with 98 million engaged Super Bowl viewers tracked by Nielsen. To reference Cecilia D’Anastasio: “That is to compare apple viewership metrics to coconut viewership metrics.” Using flimsy evidence will only mislead investors as to the actual value of titles.

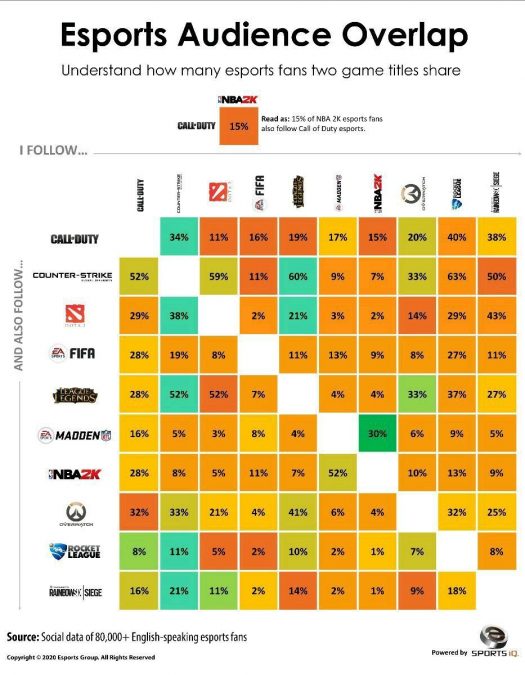

What’s more, according to an analysis by Esports Group, League of Legends shares an average of just 20 percent of its esports audience with other titles, despite being by far the most popular esport. (It should be noted that when removing FIFA, Madden and NBA 2K from the calculation, League shared an average audience of 27 percent with six other titles, including Rocket League, Dota 2, Overwatch.) The strongest overlap was 60 percent of League fans enjoying CS:GO.

If, hypothetically, something happened to League of Legends, there’s no guarantee that a League fan would engage as fully in a brand-new MOBA. There’s certainly no reason to believe they’d take as easily to an existing game; people love League because it is special in and of itself.

Moreover, fans have formed an increasingly layered connection with League esports as its history has unfolded. Faker’s dominance, NA at Worlds, Phreak’s Basement — sentimentality in sport matters, arguably more than anything else. Therein lies another endemic problem in esports: few titles are developing meaningful histories, because their shelf lives are so short. This curtails benefits derived from longevity.

Should League of Legends suddenly die, there’s no guarantee that 100 percent of that attention would transfer seamlessly to other esports. League fans might watch more movies and TV shows to fill that void. Seamless conversion isn’t guaranteed. A vacuum would appear, but could an existing title fill League’s shoes?

People care about sports, about teams and players — not industries. Approaching the esports industry as a singular entity is, in many ways, a fallacy. When we pitch investors on the industry’s value in the West, mid-level esports titles like CoD, FIFA, Siege, and now Overwatch are riding the coat-tails of League and CS:GO, and to a lesser extent, Dota 2. League fans care about League, and do not have the same attachment to Siege or Rocket League. The Overwatch League was immensely popular in the West in early 2019. Now it has lost its 2019 MVP and dozens more to VALORANT.

Evaluations of the industry simply must begin with particular titles. That goes for investors, researchers, and publications that are either being misled or misleading others.

The esports industry — this ill-defined oasis of so much joy and confusion — can only go as far as its stalwarts will take it. The key to any sport’s success is consistency, longevity, time that allows it to ingrain itself into people’s lives. If League of Legends dies, the industry’s viewership and general intrigue, at least in the West, would shrivel. Remember the Esports Group study: League shares an average audience of just 20 percent with other titles. Constantly starting from scratch halts the benefits that come from longevity, and esports is a revolving door of titles.

Accurate darts to pop industry bubbles

Maybe in time the industry’s overall viewership will total that of football or baseball. But if that engagement is fractured, each title’s money-making potential will also be capped. Sponsorship revenue will be limited, economies of scale in ad revenue will be inaccessible, coverage of each title will continue to be sub-par because outlets won’t pay the big bucks for journalists that specialise in middling titles. Moulding esports from a massive blob of promise to a few well-defined, empirically represented sculptures will mean that new money knows exactly what it’s bidding on.

League of Legends and CS:GO are huge esports that can take the industry far. Many others are “marketing campaigns for publishers,” according to Zachary Rozga, Founder and CEO of esports and gaming ad network Thece. Comparing 1880s baseball to present-day esports, he added: “Leagues in baseball were put together as marketing schemes; a paint company would play against a roofing company, for example. That’s what the current esports competitive landscape looks like to me: tournaments act as mega marketing campaigns for publishers.”

Instead of bloating the value of mid-level esports by failing to differentiate between them and more successful titles, we should focus on the mainland harvest and preserve it — League, CS:GO and potentially Dota 2 — while nurturing promising titles like Rocket League and VALORANT. CoD is far too reliant on stars and the Optic brand for viewership. Sport-simulation esports may well have a low ceiling given they merely replicate real-life equivalents. Overwatch lost dozens of Western players and broadcast talent in 2020, mostly to VALORANT. Siege had a poor 2020 after an outstanding Six Invitational.

We should avoid lumping lesser-viewed titles in with the likes of League and CS:GO when forecasting the Western esports industry’s prospects, and be more specific about where the value is. It isn’t found in the small- to mid-scale esports scenes that appear and disappear every two years: think PUBG. There are many differences between esports and traditional sports, but if we’ve learned one thing from traditional sports it’s that folklore is crucial — and folklore is borne out of longevity. For the industry to break through the stratosphere we must lean on its core pillars and sustain them for multiple decades.

When we advertise the Western esports industry, we’re really advertising two games: first League of Legends, and to a lesser extent, CS:GO (a tip of the hat goes to Dota 2, naturally). Industry folk should be more incisive and honest with evaluations; the success of competitive League is not reflective of the industry’s total value.

We should showcase the most popular titles for what they are, and avoid overrating placeholder titles. The latter may lead investors and brands to have unrealistic expectations of their ROIs, ultimately hindering the industry’s growth.