Esports organisations have morphed from scrappy startups into ambitious enterprises as the industry, despite its short life cycle, has gone through much iteration. To keep up with the changes, updated branding has often needed to follow.

Year in and year out, Esports Insider reports on rebrands that esports organisations have initiated in the hopes of honing their identity and better serving target audiences. In Q1 2023 alone, we’ve reported on five rebrands, from companies in Sweden to South Korea to Malaysia.

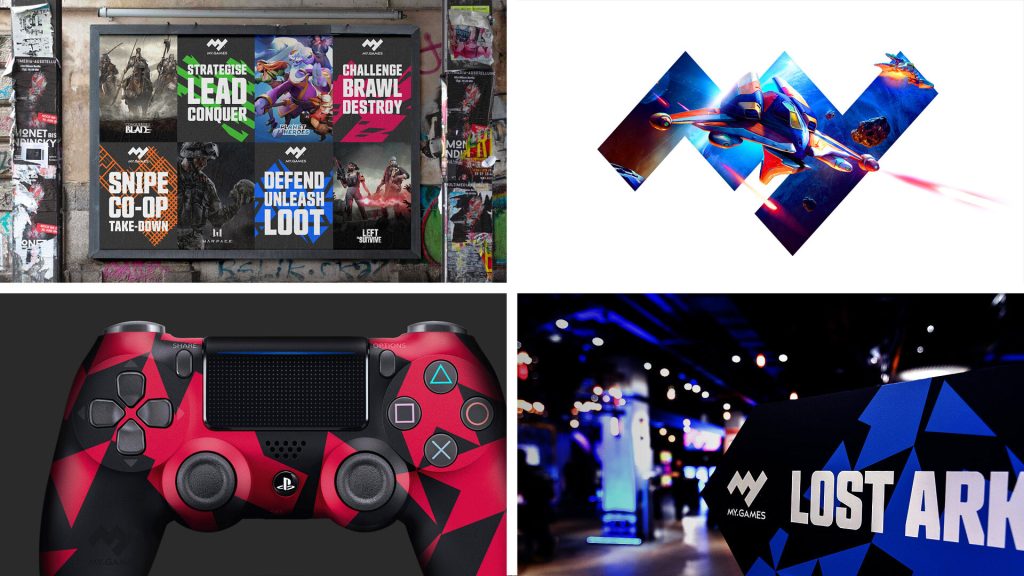

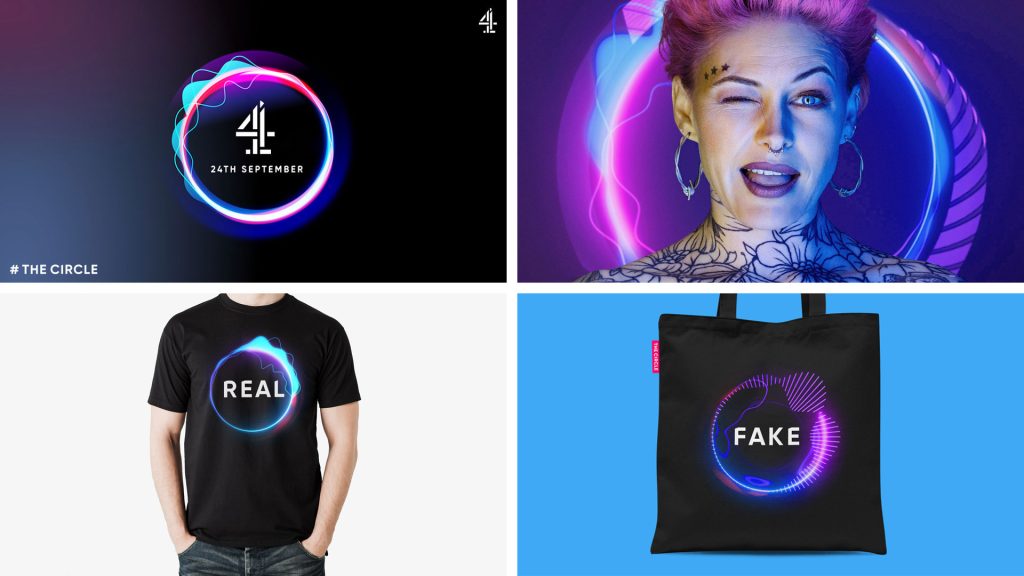

Esports Insider sat down with Turquoise Branding, a London-based branding agency, to explore the how and why of esports rebrands. Turquoise has handled branding for clients spanning the UEFA Europa League to video game publishers My.Games and Viker to TV shows The Circle, Rise & Fall and The Traitors.

Esports is an industry laying down the tracks as it goes, and over the years esports organisations have adapted and innovated to keep up with the evolution of esports and its audience.

Yet what brands are doing is nothing new, Gareth Mapp, Creative Director and Company Director of Turquoise, told Esports Insider. “The practice of branding goes back centuries and has evolved over many hundreds of years, but its core disciplines remain the same and will never change.”

Mapp explained that a recognisable brand icon that resonates with a target audience is a fundamental brand design principle, though it’s not a simple task — brands operating digitally need to incorporate several brand touchpoints that go beyond logos. “You need an extended toolkit to work in [the online] environment,” Mapp warned.

The evolution of esports branding was chronicled (and mocked) in the Paramount+ esports mockumentary ‘Players’, where a fictitious esports team, Fugitive, eventually shifted towards a modern take on its ‘classic’ old-school branding.

There’s a plethora of real life examples of leagues and teams refining and updating their branding, from the League of Legends Championship Series (LCS) in 2020, Ninjas in Pyjamas and Dignitas in 2021, Mkers, Wanyoo and Andbox in 2022, and many more seeking to revitalise their identity and better match what the org stands for in the industry today.

As brands continue to evolve, the importance of their visual identity also shifts. Nowadays, organisations are engaged in much more than just esports — and their brandmarks need to reflect this diversity.

Digital interactions between consumers and brands via social media platforms such as Twitter or Twitch now form the majority of brand touchpoints. A strong social media presence that utilises branded assets is essential for platform growth, to be sure, but Mapp believes that conveying the values of a business to the audience through robust branding principles also has enormous potential.

“From a pure branding sense, [esports teams] look like what football teams were going through 150 years ago,” Mapp told Esports Insider. “Starting up these new badges, attracting the fans, getting the brand identity set — but because this is today, the look and feel of these brands is all today.

“The target audience is very young, so you get that sort of irreverent feel, with that sort of manga and comic book attitude and all. Which is cool, it’s really cool,” Mapp opined.

The hurdles that come with rebranding

Although rebrands can give short-term boosts to social media metrics, they often do little more than tweak logos and brand marks — which Mapp refers to as the “shorthand of the brand.”

As esports companies across the board come to terms with a need to diversify, and new business verticals become an unavoidable necessity as a result, companies can benefit greatly from well-planned branding processes. Rather than undergo yet another ‘esports rebrand’ for the sake of it, Mapp said these branding processes should be premeditated and deliberate if they want to yield versatile and sustainable results.

Whether subtle or dramatic, branding changes can be extremely divisive amongst esports fans, at risk of triggering a Twitter storm if it misses the mark. Rapid rebranding also implies that design choices are ill-considered and badly planned. One particularly famous example was Evil Geniuses’ notoriously poorly-received rebrand in 2019.

All branding aspects, especially in the digital realm, should be approached with care. To illustrate this, Mapp cited Turquoise’s UEFA Europa League rebrand, in which the agency created a “massively versatile toolkit, almost a modular system, that allows for infinite variation in the identity.”

This multifaceted approach allows the brand to stay fresh. The system is more a visual language, rather than pre-made designs, that intuitively inform and delight viewers.

Turquoise’s design philosophy emphasises creating distinctive and ownable visual languages for brands. “If you look at [TV show] The Circle, it has a logotype, but that moving, animated circle is what we call a brand property,” Mapp said. “It gives a flavour, a more emotional and expressive feel to the brand.”

A good brand identity is flexible, allowing for animation, cropping and playfulness rather than a logo sitting still in a corner, Mapp added. A brand property enables the audience to recognise the brand without having to see its brandmark, name, or logotype. Tournament organiser BLAST’s events, for example, often feel like BLAST events without even seeing the logo.

Mapp highlighted the depth of branding in esports. As you zoom in, each layer of the esports ecosystem — titles, leagues, teams and players — reveals its own unique branding.

Larger-than-life professional players, such as Faker, TenZ and Hungrybox, have their own personal brands that drive distinctive narratives in esports. Some pros tie themselves to the esports organisations they’re signed to — it’s hard not to think of Fnatic colours when you think of Krimz — while others carry their own strong branding independently of their team.

This individualised, personal branding — and the way teams play on it — is a page taken from traditional sports’ playbook, Mapp noted. “This personal branding in sports all started with [Michael] Jordan. He became bigger than the team. Then what the Chicago Bulls did, which was quite clever, was they upped their game which attracted more star players, and then all of a sudden you have this huge global brand.”

Older and larger esports organisations have deeper roots to anchor them against trends and fan preferences. All are navigating their branding in real time to accommodate rosters of diverse player histories, personal brands and the changing tides of esports audiences.

As they navigate particularly tricky waters and contend with an ever-evolving audience base, — and try to win a few games at the same time — adhering to best-practice branding principles will be vital.

Supported by Turquoise